I. Introduction

In this post, I want to talk about moe, or more specifically – problems I’ve seen concerning a certain trend in regards to anime and sexuality. I feel that this problem has been bubbling under the surface for a while now and most people either don’t know it exists or, if they do know about it or are aware of it, don’t know how to talk about it. Here I plan to demonstrate a few things that are exclusively problematic to anime and how to address them, most notably, that the anime-to-LGBT pipeline does exist and is a threat to lonely, isolated people (not to mention minors and people struggling with mental illness). What I won’t be talking about are problems associated within subsets of the anime fandom, such as anime-themed Discord chat groups or gossip concerning popular YouTubers who just so happen to be associated with anime fandom. Rather, I’ll be talking about this phenomenon from a much broader perspective in the context of moe, otaku culture, and parasocial relationships.

II. Moe and the Otaku Problem

A common misconception among artists and even some fans of anime is that moe is an art style. This is an easy mistake to make as the term itself is typically associated with features that make anime art “moe” (e.g. large eyes, a round face, a small nose, “babyface” features, et cetera). Moe, when used correctly, is used to express a feeling or an emotional response to specific stimuli (typically a sensation that is warm, comforting, and affectionate in nature). As such, it’s important to note that the feeling moe gives to an individual can be in response to seeing a specific character, to images of said character, to even ideas. Japanese cultural critic Toru Honda - when describing the phenomenon of moe in manga and anime - describes moe as “imaginary love (nounai renai).” He notes the effect the moe character gives to the viewer of being a type of “perfect love.” Thus, Honda is “married” to the fictional Kawana Misaki from One: Kagayaku Kisetsu e (One: ~To the Radiant Season~).

As a fan of the work of Kiyohiko Azuma (Azumanga Daioh, Yotsuba&!, and others), to say that I have felt the response that moe was meant to give would be an understatement. I felt (and still feel) a sense of calm and peace when I revisit the innocent, carefree adventures of little Yotsuba and her friends and family in Yotsuba&!. Watching Azumanga Daioh brings me back to highschool (even if the show barely resembles my own experience). I’m brought back to a time when I could look forward to seeing my best friends and make memories without realizing that those moments were the happiest moments I would ever have. This is all to say that I absolutely do understand the appeal of moe and do find value in it. Moe, from my own experience, has been a tool used to saturate my mind with positive thoughts and emotions - substituting unwanted memories with a rose-tinted nostalgia that appeared to exist if I could imagine it. That said, the experiences and emotions that these shows offer cannot substitute the very real need for validation and intimacy that humans crave for one another, after all, we are social animals. Whether that need was deprived in the past or is currently not being met in the present, moe can try and fill that empty void in the heart of the lonely, isolated man, but it’s a very shallow form of “love.”

Toru Honda, on the other hand, does not desire another person’s company or companionship. Instead, voluntarily choosing to live out his life in the two-dimensional space (hence his “marriage” to the character Kawana Misaki). In an interview with Mammo.tv, Honda explains what his concept of “love capitalism” is, and how anime helped him cope with being rejected from his peers and wider society.

In this society where love is equivalent to modern capitalism, all the parameters required to “win” in a capitalist society apply to love as well. I’m talking about things like your economic value and your academic history. That and your looks. Humans have biological urges, so that should go without saying. People who lack either quality would have to sharpen their communication skills—things like their personality or hobbies. And since the late 80s, the one’s deciding the rules of the dating sim would be the advertising agencies and the mass media. Magazines with dating advice like Hot-Dog PRESS were selling well, and the trendy dramas and Hoichoi films were spreading all over the place. The contents of those products created the dating sim known as “reality”.

It should be noted that Honda is a self-identified otaku. Honda came to prominence when he harshly criticized the themes of the film Densha Otoko - a film where a socially awkward, Japanese nerd goes through a hero’s journey after saving a woman’s life on a train. This, he believes, was a betrayal of what otaku is. Otaku are disadvantaged, they are the nerds and geeks who did not choose to be outcasts, but were made outcasts by various circumstances. Thus, the otaku is someone who has come to reject society and chose instead to live their life through interests (most notably anime and manga).

In the same interview Honda makes two points that could help us identify both the consumer’s (otaku’s) role and the product’s (moe) role in establishing this 2-Dimensional relationship.

- The motenai (モテない “unpopular man”) is disadvantaged in life, and cannot compete with those who already have status, wealth, academics, etc. And because everything from romance, to careers, to ordinary relationships are seen as transactional, the motenai’s only option, then, is to seek solace in the realm of fantasy. Thus,

- Otaku stop caring about what is socially acceptable and what is not. They typically become NEETs or “hikikomori” (ひきこもり) or will find work through unconventional methods. They may hold fringe political beliefs or philosophical beliefs about the world and life itself.

In this way, moe can be seen as the ultimate coping mechanism. In writing Dempa Otoko (a refutation against Densha Otoko), Honda argues that moe can help the motenai and the himote (otaku who are unpopular with women). He calls for the end of real life romance and sexual relationships in favor of the 2-Dimensional relationship dynamic that moe provides with fictional characters. Seeing moe as a way for men to escape societal expectations placed on them, Honda goes on and argues for men to seek alternatives to conventional masculinity. A moe man (moeru otoko), for instance, can embrace his feminine side by taking care of moe characters with a type of love only found between a parent and child without the worry of having his masculinity being challenged, judged, or questioned. Anyone can become a moe man, from the Japanese hikikomori to the American ‘incel.’

Going back to the word otaku - the word has an interesting place right now in anime fandom, with some embracing it with full sincerity while others prefer other terminology such as “weeaboo” or “enthusiast.” While being a self-identified anime nerd nowadays (whether in the East or the West) isn’t as frowned upon or taboo as it once was, being an otaku in the past came with its own set of negative connotations. Journalist Akio Nakamori, who is credited with helping bring the word otaku to the mainstream with his column Otaku no Kenkyuu (「おたく」の研究 lit. “Otaku Research”) in Manga Burriko in 1983, said the following when describing these types of fans:

“Otaku definitely lack male skills. So they are satisfied carrying photographs of anime characters like Minky Momo and Nanako. I would call it a two-dimensional complex. They can’t even talk to real women. In less extreme cases, they orbit around idol singers who do not show their femininity, or pervert and enter the lolicon. These guys will never accept a picture of a naked mature woman.”

Nakamori’s perception of otaku is much more negative, uncharitable at worst - believing otaku to be weak men who haven’t grown up (or, to use a more modern phrase “manchildren”). It’s hard to discern whether Nakamori believes otaku men should conform to a more traditional masculine identity for their own sake, or if he believes that the typical otaku is simply incapable of making such a change and is therefore destined to be an otaku. On describing the stereotypical otaku from an outsider’s perspective, Nakamori makes the following observations:

“The boys were all either skin and bones as if borderline malnourished, or squealing piggies with faces so chubby the arms of their silver-plated eyeglasses were in danger of disappearing into the sides of their brow; all of the girls sported bobbed hair and most were overweight, their tubby, tree-like legs stuffed into long white socks.”

Nakamori’s (as well as the average Japanese citizen’s) general consensus of what an otaku was would ultimately culminate into their worst nightmare in 1989, when Tsutomu Miyazaki was found guilty of having raped and murdered four elementary school age girls. It appeared nothing was off-limits for Miyazaki, as not only would he kidnap his victims, but he would molest and dismember the bodies of his victims, mutilate and eat specific body parts, and later mail the parents of the victims with ominous messages about what he had done. The connection to Miyazaki and otaku was made when a search warrant was issued and police found boxes of anime and manga reaching the ceiling of his house, with hentai manga near his bedside.

This negative perception would last throughout the 90’s and would only subside during the 2000’s when otaku were seen as a new economic driving force; their purchasing power allowing sales of not only manga and anime, but apparel, CDs and DVDs, and other merchandise to help fuel new creative endeavors and keep animation and manga jobs in demand.

From here it may seem that Nakamori and Honda may come from the complete opposite ends of the social, economic, and status spectrum of success. On one hand, we have Nakamori who sees himself as the anthropologist or zoologist of the otaku, carefully researching a strange creature’s movements, patterns, and behaviors, trying to understand it while being careful to not become like it. On the other hand, we have Honda, who - after coming to better understand himself and his life after reading the likes of Neitzche, Kierkegaard, and Descartes after dropping out of high school and working menial labor to survive - embraced his otaku-self and became a philosopher, leading him to reject the majority of social norms such as marriage, child rearing, and the rat race.

Honda’s idea of the unpopular man (motenai) aligns well with the otaku or the hikikomori. The possible distinctions among otaku arise then in how they let their perceptions about themselves shape their life. In Honda’s case, one could argue that - instead of appealing to modern sensibilities of what a man should be - he instead chose his own path. Being born neurodivergent as well as unattractive - it should be made clear that Honda was dealt a bad hand in life through no fault of his own - and that no amount of sympathy, hard work, or education would have changed him into a moteru (モテる"popular man”) much in the same way one cannot simply “grind away” or “grindset” one’s problems away and rapidly change from living as a “blackpilled volcel” and start living as a “gigachad.” And so with moe and philosophy being his only source of comfort away from reality, Honda (instead of viewing himself as a loser), chose self-acceptance and non-attachment.

However, both Honda and Nakamori fail to address the central problem of the otaku-moe relationship. The moteru, although seen as a success by women - should be careful to not use his good looks and material wealth only to then disassociate himself from women on a physical, emotional and spiritual level. This is the problem with materialism and hedonistic pleasure - and while the otaku is not immune to this because he lacks access to women - the moteru should be even more considerate of his actions since he is in danger of believing he is entitled to sex, entitled to pleasure, entitled to the things that others don’t have the luxury or privilege to experience. The motenai, on the other hand, faces the danger of succumbing to idolatry and porn addiction - putting an image or representation of a woman (in the otaku’s case, an anime woman) up on a pedestal. In Honda’s case where he has rejected contact with real life women and has married a fictional character, devoting his time and income to a manifestation of the “perfect woman,” it should be rather obvious that he has crossed the line from mere interest or fascination with the Kawana Misaki character into worship and devotion.

Ultimately, what moe gives these men who prefer their virtual existence over real life is an idyllic representation - a desired life or even an ideal person that can only exist in the 2-Dimensional plane. Thus, when discussing moe as a way of life and its relationship with those who choose to exist only with moe in mind - we begin to see moe not as temporary relief from the real world - but as an ecosystem where we indulge in fantasy and ignore our own reality. This is why moe is so appealing to its audience. It’s safe, comforting, warm and friendly unlike the harsh realities of economic instability, the decline of religion and culture, the uncertainty of war, etc. Although moe has a generational appeal to children and adults alike, the fantasy that moe provides allows adults (in particular, otaku) to retreat to a corner of the world where people, objects, and environments behave in expected patterns. There are no sudden tonal shifts or intense dramatic moments found in the likes of K-On! or Lucky Star. An adult, working male doesn’t have to come home to worry about his favorite character since most moe anime occupies the same space as the “Slice of Life” genre (with iyashikei “healing manga” being a subgenre of “Slice of Life”).

III. Moe's Narrative Problem

As much as I enjoy Azumanga Daioh and wouldn’t want to change it - I must be fair and acknowledge that the characters I’ve liked for a long time are tropes. Tomo-chan is a genki girl, an energetic, hyper teenager who’s loud and rambunctious. Osaka is an aho girl, she is soft and sweet, but aloof and could be considered an “airhead,” or “birdbrain.” Both characters I just mentioned are archetypes - simplified versions of everyday people we encounter in real life. If I were to equate moe with my own life, it could be very easy for me to reduce the girls I became friends with and had the most affection for in high school as being the genkis or the ahos of my life. These girls I have memories of are thus not real anymore, but are now just moe. But doing that would effectively box real people into categories or stereotypes - and while sometimes stereotypes do exist for a reason - no one person neatly aligns with all the possessed traits of a given stereotype. Doing so would be a form of objectification, a way of reducing the dignity of a person.

I mentioned earlier how the majority of moe anime can be categorized as “Slice of Life”. That is, they’re typically episodic, comedic shows with no heavy plot. You can begin at any episode and get the general idea of who the characters are and what the show is about as there are no dramatic character arcs or intense, heavy narrative to keep you invested in the show. This is a double-edged sword, as it makes the moe characters flat as a board in terms of personality. However, because of this - they become an easy object to project emotions and desires on to.

“Tomo-chan wouldn’t act like this in the show, but in this scenario I’ve created, who knows how she would respond?”

From our understanding the perspectives of both those who disavow the otaku life and those who embrace, the one thing they agree on is that those who choose to devote themselves to the world of fiction and fictional characters will inevitably develop a two-dimensional complex (nijigen konpurekkusu). Hiroki Azuma - a novelist who is critically aware of this issue - describes moe (and otaku culture) as a type of relationship dynamic that is “dissociative.” He states that otaku “learn the technique of living without connecting the deeply emotional experience of a work (a small narrative) to a worldview (a grand narrative).” Azuma notes that for the feeling of moe to take effect, narrative must be distilled and subdued so the viewer can focus on the characters that produce the moe effect. If the response still needs to be stronger, then individual parts that produce the moe effect will be heavily emphasized (rather than the character). “Since they [otaku] were teenagers, they had been exposed to innumerable otaku sexual expressions: at some point, they were trained to be sexually stimulated by looking at illustrations of girls, cat ears, and maid outfits.”

Thus, we see problems arise not just with moe - but with fans who consume moe. Whether these characters lacking any real depth is intentional or not, the consequence is still the same, in that many fans will reduce these moe characters to neat little fragments, easily digestible attributes that don’t need any further thought or consideration put into them. Despite being one of the most complex characters in the show with a fascinating origin story and end to her narrative, Rei Ayanami is reduced to her sex appeal and to the simple archetype of the dandere (the silent, expressionless type). In the West, the word “Flanderization” was coined in regards to animated characters and their loss of self. The term was named after Ned Flanders from The Simpsons – a father, small business owner, and overall good neighbor who just happened to be a typical, suburban American Protestant. The loss of complexity and personality of characters such as Ned Flanders made him an easy target for writers who had no interest in Protestant Christianity or religion in general. With each new season came new writers who received a different Ned Flanders who was less of himself as parts of his personality was watered down and simplified. He became nothing more than a caricature. At worst, he became a strawman of the religion the writers would unleash their frustrations against (mind you, it was never Christian theology or beliefs that were attacked by the writers, but the perceived ideas of what Christians held to be true that was attacked - much in the same way the writers use the character Starlight as their mouthpiece when she denounces her faith in Amazon’s The Boys).

With Western animation - the concern the audience has with media and fandom in general is canon and consistency. With Eastern animation, although canon is important - what appears to be even more important is whether the characters can fulfill the needs and desires of the consumer. These needs may be emotional, romantic, or sexual. Moe and “kawaii culture” have bridged this gap between various subcultures with the creation of trends such as “erokawa (エロカワ)” and neko (猫娘) or catgirl eroticism (in the case of catgirl fetishism with its use of leashes and pet names, it could be argued that this is a “lighter” or “softer” version of BDSM). This poses a large problem for casual fans of moe as a whole. Moe does not have distinctions or categories - nor does it try to segregate itself away from adult-oriented themes and motifs, as that is the primary consumer demographic. Rather, a concerning pattern arises where moe is seen as an invitation into a much more perverted, lonely world where hedonistic pleasures come first.

In some ways, the blame could be on the part of moe and moe creators themselves. If the design of a moe character is intended for the simple pleasure of visual and emotional satisfaction (i.e. Honda’s description of moe as “imaginary love”), then it’s very easy to understand how the otaku can justify perverting said character he “loves” without shame. If everything from the design of the character to the personality is all but an empty vessel, then it is not a true character the otaku or weeaboo is interacting with, but an emotional prostitute. “Waifu culture” takes this to the extreme, with men devoting their time, income, and emotions into an artificial woman or harem of women who cannot feel, see, or care about them. These men will spend money on art prints, dolls, and body pillows to have a sense of their waifu’s presence, read fanfiction so they can imagine themselves with their waifu, and will watch scenes featuring her from whatever show she appears in so they can feel that less alone.

If this all sounds crazy to you or if you feel like I am exaggerating, then look no further than gacha culture. The success of “games” such as Genshin Impact and the Honkai franchise are a perfect example of what Azuma calls “database consumption.” That is, whether they realize it or not, consumers don’t need or even want fleshed-out, realistic characters or worlds to immerse themselves in. Rather, they want “elements” from the database - tropes (the dandere, the tsundere, the nadeshiko, etc.) Individuality of character (and thus, the author) is erased in favor of the predictable and repeatable.

The database animal – the consumer of the product – can categorize these characters into elements which can then fit into the larger database. Rei Ayanami loses herself as her origin is flattened and reduced over time with similar characters being created in her shadow. Rei Ayanami is not just one character, but also Yuki Nagato, Yin, and Kanade Tachibana. Likewise, flat, lifeless “characters” fill the universe of gacha games with their paper-thin personalities. Many of them are well-designed and look attractive in official artwork and fan illustrations, but gacha games are not an invitation to an unforgettable story or even to an incredible world that’s full of mystery and lore - rather, it’s an invitation to a soulless, corporate machine that uses beauty and aesthetics to drain you of your income. If moe is the heart, then gacha, virtual novels, v-tubers, and AI chatbots are the blood vessels pumping life into the system of emotional exploitation.

IV. Moe & Sexuality - The Otaku to Homosexual Pipeline

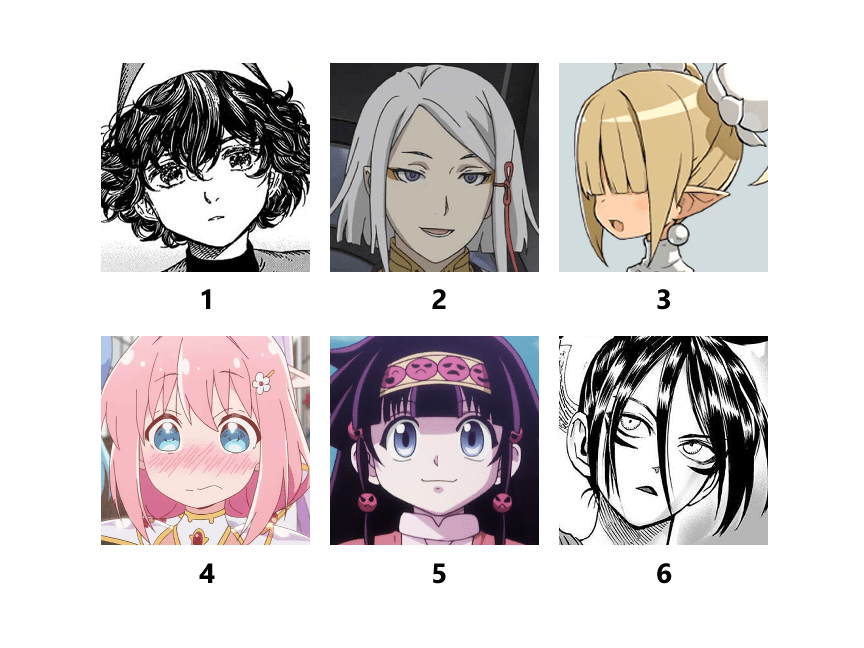

I want to play a game with you now. Using examples of moe character design from various anime and games, I am going to share some characters with you and ask you what gender the character is just by looking at their face. The answers will be down below.

And here are the answers:

- Female - Agott (Witch Hat Atelier)

- Male - Dio Eraclea (Last Exile)

- Male - Male Healer (Disgaea)

- Female - Juulia Charldetto (Endro~!)

- Male - Alluka Zoldyck (HunterXHunter)

- Male - Speed-o’-Sound Sonic (One Punch Man)

So why did I have you do this? If you guessed the genders of all the characters correctly - I’m impressed. You probably have watched a lot of anime or have had just enough exposure to be able to differentiate between “male” and “female” character design elements. If you didn’t guess them all correctly - think about why that was. Was it the style the character was drawn in? Did you have an expectation for a male character to look a certain way? Did you come away thinking: “There’s no way that character’s a dude?” If you had any doubts or were unsure of yourself I don’t blame you either. As reality is trying to distort and blur the boundaries between the sexes with matters such as “there being more than two genders,” it’s no wonder why those who believe in concepts such as non-binary gender identities will flock to anime where they can partially live out their fantasies. But before we delve into that topic we must first talk about the problems that these design elements can cause if left unchecked.

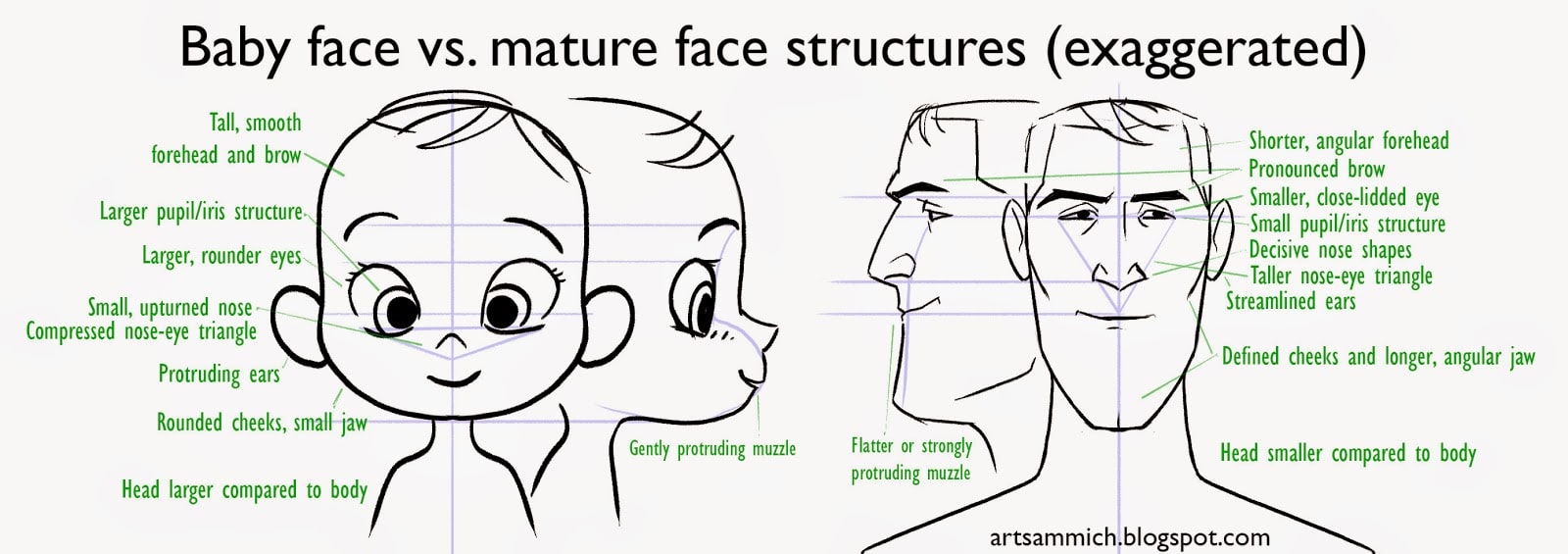

Part of this confusion comes from design elements that make moe so effective; the rounded, soft features of the characters, delicate lines, smooth shapes, and visually appealing, attractive faces. Sam Nielson - who works as a concept artist and character designer for companies such as Disney, Blizzard Entertainment, Skydance, and various other studios - calls this the “baby-face bias,” illustrating a simple example here:

He says: “a baby-face says the character is naive, helpless, and forthright. We naturally see that character as having a not-completely-formed identity, or as having an identity that is not yet defined.” He goes on, however, to state that the facial design elements are not strictly tied to childlike characters. Rather, the design choices are intentional to reflect the character’s personality regardless of age or sex. “Most [designs] mix elements together to achieve a character that combines the right elements of experience, capability, innocence, and development.”

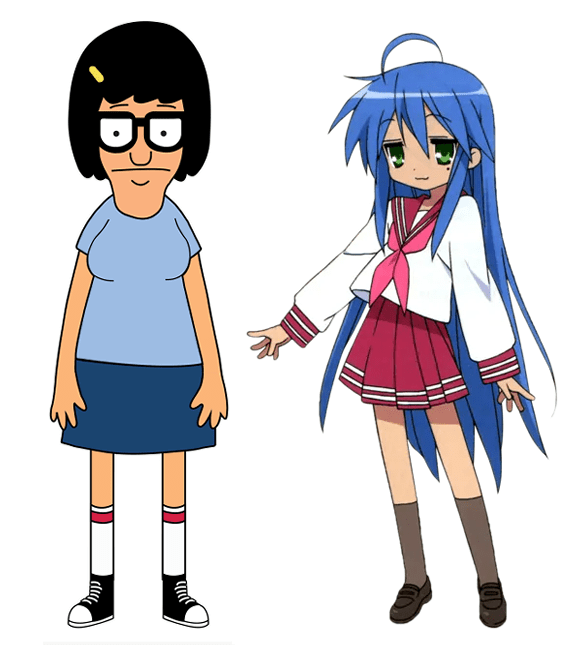

Nielson spoke about the face and the overall design of the character as being a reflection of the character’s personality (as this has been a standard in Western animation design philosophy for decades). With Eastern design philosophy (I admit this is just pure speculation) the motives behind designing a character are its visual appeal. How cute can we make this character? How attractive or marketable can we make this character using aesthetics alone? For comparison, let’s use two teenage girl characters.

Tina from Bob’s Belchers is not designed to be attractive. Everything from her weird, pear-shape body, her haircut, to her choice of clothes show that she is an awkward, nerdy outcast. She is not the romanticized concept or the ideal fantasy of the teenage high school girl, rather, she’s a caricature of a modern, boy-crazy girl who’s just as plain or ordinary as anybody else. She doesn’t have any special or unique quirks that really make her stand out - and so her design reflects that. Compare this design with someone like Konata from Lucky Star. Konata is supposed to be an otaku, not necessarily an outcast or a loner, but a nerd nonetheless. Her design, however, says the opposite. Everything from her long, blue hair, her large green eyes and short body, to her face and school outfit all shout moe. Some may argue that that is the point, this is Lucky Star we’re talking about after all. But I argue that no matter which show we’re talking about (K-On!, Azumanga Daioh, Nichijou, Watamote, etc.) all of the characters are virtually identical.

With the examples I’ve given, it should be apparent by now that moe and the audience that consume moe are primarily interested in aesthetics and attraction. By now, you might think I have an issue with beauty itself - but I don’t. What I do take issue with is the oversexualization and perversion of that which should be treated with dignity (more specifically, the body). If we think of artists that heighten and elevate the natural beauty of the human form (Michelangelo, Rembrandt, Da Vinci, etc.), then it’s important for us to consider art forms that are reductive - art styles that objectify the human form for selfish pleasure (especially those art styles that create with the intent of sexual arousal).

I’ve spent a good deal of this article talking about real men’s interactions with fictional female characters, however, that doesn’t mean that male moe characters are immune to these same problems that female characters face. Now what do I mean by this? Both Azuma’s and Nakamori’s diagnosis of the otaku problem seemed to be addressing the common problems of emotional deprivation and unmet sexual desires of isolated, lonely men. And although most attraction for moe characters is felt through female characters specifically, the design elements that make moe work so well can make a male character have the same emotional and sexual appeal as a female character. What needs to be understood is that - as a design philosophy, the effect of moe can be applied universally to any or all characters (male, female, or otherwise). We as humans like to think of ourselves as being more perceptive than we really are, but our brains don’t always pick up on subtle cues or little bits of distortion in reality. Our brains can play psychological mind games with us to handwave away subconscious feelings that are very real, we just don’t realize it. This goes back to the game I asked you - the reader - to play earlier.

This is Kurapika from HunterxHunter. This is not a human male. This is a representation, an abstraction of a human male in a drawn form that our minds read (and thus, believe) to be male. All “he” really is is ink on a piece of paper, but all of the forms, shapes, and feelings associated with him and his design register to us as being “almost human.” The most gorgeous or most handsome of androgynous males with neotenous features will never be able to compete with what our limitless, human imagination can create. The design elements of moe and kawaii culture in general make this a very easy thing to do. You might be asking why I chose Kurapika from HunterxHunter instead of a character that is more recognizably designed to be moe such as a character from Nichijou or Strawberry Marshmallow.

This is because Kurapika perfectly encapsulates the very real danger that moe presents to us as readers and artists (I write this as someone who has a lot of affection and care for the character Kurapika, as well as Gon and Killua - so don’t take this as me hating HunterxHunter or Togashi). The problem starts when we look into a popular portmanteau created when Kurapika gained fame in Japanese online spaces - notably, Pixiv. The portmanteau in question is “Kurapikawaii” (クラピカワイイ).

From this tag we get a feminized Kurapika. Instead of youthful masculinity being the center of his design to help produce the moe effect, what we have is artwork created that reflects a type of gender ambiguity that only moe can create. In the above fan made image - Kurapika - instead of having his characteristic “cat-like” eyes (a reflection of his tragic past as well as a design element used to show his sharp, focused mind) - now has tareme eyes (タレ目) or “puppy-dog eyes” similar to Yui from K-On! His sharp, pointed features have been softened, what muscles he did have have been reduced or flattened, his hair becoming soft and looking like he just came back from a salon rather than a fight. I’ve only scratched the surface of this tag, but nonetheless, if you search more and more fan art, you will inevitably find fan art that exploits these moe design elements to make Kurapika as kawaii or as feminine as possible.

The problems don’t end here. From a little more searching we get the “Gender:Kurapika” (性別:クラピカ) tag. A Pixiv definition of this tag reads:

Kurapika's appearance is very neutral, and his face can be taken either way in the original work or in secondary works...The author himself commented on Kurapika in HUNTER x HUNTER Anime Tsushin Vol. 1: “It seems that I have [made] a character who is more difficult to tell whether he is male or female than I had imagined...” he commented in response to readers' reactions.

I won’t comment on Togashi’s intentions when designing Kurapika as I just don’t have the time necessary nor the information to really say one way or the other. I’ve tried my best to limit speculation to a minimum in this article, and so I won’t comment on Togashi’s creative process or thoughts on Kurapika. That said, Togashi was born in a country saturated with moe content, however - he created a rich, beautiful world with a powerful, memorable narrative with characters that have stayed on the minds and hearts of its readers for decades now.

However, notice the above definition which defines Kurapika as having a face that “can be taken either way.” If that’s true, why should my original statement of him being a representation of a male even matter? Keep in mind, we’re talking about a character who is canonically 17, meaning he’s still a minor through the majority of the HunterxHunter canon. This is why I had you play the “Guess the Gender” game earlier, as moe perfectly synthesizes what we consider to be universally attractive and cute. Whatever features of a person or type of person you find cute, moe will enhance those traits to its maximum potential (the genki girl, the kuudere boy). This design philosophy not only applies to the personality of the given character, but also to the body and - most importantly - the face. If on male characters we find a strong jawline, clear skin, and sharp eyes attractive, then moe can either enhance or simplify those features to a degree that we can still recognize a character’s gender without noticing the subtle ambiguity or androgyny.

I want to stress now the importance of this transformation or moe-fication we saw of Kurapika. We just learned that fans of Kurapika noticed the subtle gender ambiguity of his facial design, and thus created words and phrases associated with that design. A major issue with this is that HunterxHunter is not the only manga that has this problem, in fact, I argue that this is a problem systemic to a number of anime and manga regardless of the genre. This type of blurring of the faces (or, “same face syndrome” as artists call it) – if not handled carefully – creates a problem where sex and sexual attraction is fluid. The slippery slope of moe distorts the definition of what is male and what is female. A moe face has no gender, it is its own gender - so long as it causes the needed effect of emotional desire and “imaginary love.” Anything can be moe since what can or cannot cause the moe effect is virtually unlimited. Unfortunately, the consequences are either realized too late or not noticed at all, being blamed on something else entirely or handwaved away as seemingly unimportant.

If the face becomes androgynous and can be used as a way of maximizing emotional or sexual desire on the viewer – then the body can be distorted to fit whatever needs that viewer has. As we see above with the uncanny resemblance between Deku and Ochako in their face, it’s not hard to then come to the conclusion that the two of them are virtually identical. The only thing that separates them is their personality and sex, but can we be certain that the response moe stimulates can be regulated to one’s innate sexual preference? Once again, let’s use Konata from Lucky Star as an example.

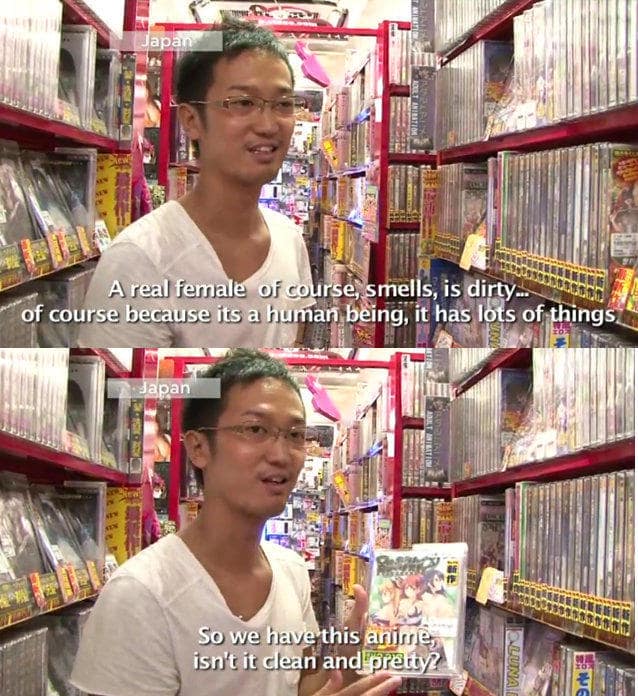

It’s not the otaku’s fault for looking at her – first wanting to protect and care for her – only to then start developing feelings of sexual attraction later on. That is what moe is designed to do and what makes it work so well. If we take everything we’ve examined so far - from Honda’s idol worship of his imaginary wife, Azuma’s description of database consumption, to Nakamori’s observations of otakus – then our only conclusion to make is that moe can and has been used as a mechanism for change in human sexual behavior. The more intense the moe effect, the more intense the human response is.

A heterosexual male, for instance, who may have once felt only emotionally and sexually attracted to female characters may inevitably find themselves sexually attracted to male characters. As we’ve seen with the Slice of Life genre and characters such as Kurapika, moe gives us the ideal character, a personification of our inner wants, desires, and fantasies. If this person is the type to distort fiction and reality even on a subconscious level, then they may come to believe that their sexual persuasion is not heterosexual, but something else entirely. Some may assert that their attraction to moe can still be managed or governed to specific traits (i.e. blonde girls, shy girls, etc).

I argue that while that may work for some people (such as casual fans) - it definitely won’t work for the otaku or the weeaboo who has made anime a core part of their identity. As I stated earlier, moe does not make any attempt whatsoever to distinguish itself from ecchi or hentai. If we consider just how alluring and addicting pornographic content online is, then we should see moe as an invitation to more intense content that will satisfy the lonely, emotionally-void hearts of those who indulge in such media. If you’re already attracted to long hair and feminine facial features - what’s to stop you from being attracted to a male character with long hair and the exact same face as a female?

That type of character (as you might have already guessed) is called a “trap” or otokonoko (男の娘). And it should be obvious to anyone else that the majority of these characters only exist for fetish reasons. While it could be argued that at least otokonoko could be based on a specific fashion or lifestyle in reality, there are very specific sexual paraphilia that only exist in the realm of anime. Sexual attraction to outrageously large breasts, half-human-half-animal hybrids, fantasy scenarios involving monsters or aliens, the list goes on – all of these unnatural desires are only possible because of anime.

In regards to otokonoko, the old idiom: “If it walks like a duck, looks like a duck, and quacks like a duck, then it is a duck” does not apply. The effect of moe and the stylistic features of moe characters overwhelm the otaku, conditioning the sexually frustrated individual to become confused about his own sexuality and addicted to more stimuli than he can count. A trap has a much different effect on a person and has a different reason for existing as compared to a character like Bugs Bunny wearing women's clothing for comedy’s sake. We’ve crossed the threshold of parody and satire a long time ago and are now in a state where what is “male” and “female” are meaningless attributes assigned at birth that can be ignored. We’ve come to reject reality and what God has given us and instead choose to live a selfish life where man is at the helm of creation.

Many will downplay the effects fiction has on the mind believing that, because it’s not real, then it must be harmless. They will point to critics like Jack Thompson who blamed Grand Theft Auto V as the central cause for the Navy Yard shooting – and that anyone who takes issue with their favorite video game/anime/show and its themes or content must therefore think just like Thompson. But we’re not talking about extreme acts of violence nor are we talking about the many variables associated with what could make someone a mass shooter. We’re talking about a demographic of lonely men who are being exploited for capital. Instead of arguing whether media causes violent behavior, we should instead examine how violent, graphic content has become destigmatized, almost normal in a society we believe to be “more civilized.”

When discussing the slippery slope, it’s important to recognize that we’re not talking about “chasing the next high” or being in constant need of a dopamine rush. What we’re talking about is gradual acceptance over a long period, sometimes referred to as “creeping normality.” Someone may start off as a casual anime fan watching typical shounen anime like Dragonball Z. This person may then find themselves more accepted in the anime community, and so they don’t mind calling themselves an anime fan. Later on they watch Evangelion and other shows of their interest, only to later watch shows outside of that genre out of curiosity – at this point, they’ve also accepted the endearing term “fellow weeb” as a part of their identity. This person has already been exposed to enough stimuli reminiscent of moe (be it moe girl characters or ecchi fan service) that something like Clannad doesn’t appear foreign at all, it doesn’t register as anything different in their brain – it’s just more Dragonball Z. The slippery slope has allowed enough foreign material and ideas to be normalized and we see a pattern emerge of tolerance, and once that happens, the gateway opens up for perverse, sexualized content to seep its way in. For those who already indulge in pornography or are just vulnerable people – it won’t be long until something like lolicon or futa – now in their vocabulary and their thoughts, is now in their browser history or hard drive.

V. The Response

So far throughout this post, we’ve examined what makes an otaku an otaku, and what moe is and what makes it so powerful. We’ve seen just how easy it is to use the stylistic features of anime art styles to induce unwanted sexual behavior changes in fans. As well as this, because anime and anime content has become a normal part of their lives, they fail to see any reason to challenge anything that may be subversive, obscene, or even immoral within the anime fandom itself. It should be worrying that a manga such as Made in Abyss gets praised for its storytelling and cast of moe characters when those same characters are being traumatized mentally, physically tortured, and sexually violated all for the author’s pleasure, but it’s all accepted so long as it is masqueraded under the veil of “horror,” “shock value,” or “just being edgy.”

So what’s the response? What am I – someone who still watches the occasional anime and has his favorites – to do? I’m not asking you to quit watching anime altogether, to throw away your manga or DVD sets, or to sell some of your merchandise. What I am asking you is this: “Where do you draw the line?” That is, what have you personally tolerated for so long that you otherwise realize is unnatural and undesirable? Are there specific ideas or paraphilias you don’t want to be attached to anymore? Are there concepts that you’ve come to tolerate without you’re being aware? Then it’s time to lessen that attachment by removing yourself from the nearest occasion of that behavior. Have an attraction to otokonoko? Then you need to stop visiting websites or adult-oriented imageboards that allow that material. Ideally, stop using words like “trap” or other words associated with that fetish in your vocabulary. This is much more difficult than it may seem (especially if you struggle with addiction), but these first few steps will help a lot.

Are you an artist or someone who wants to write a light novel? Try thinking of characters not as tropes or, going back to Azuma – learn not to think within the “database of consumption.” A common tip for writers is to “write what you know,” and while this may seem like generic or boring advice, when we take time to actually investigate inward and ask questions about ourselves, to begin writing for our own sake, then the fruit will come naturally rather than relying on ideas already created within the database. For artists, think of your character (or the character from your favorite anime or manga you wish to portray) as being a real person deserving of dignity. What is their background? Why are you depicting them in this situation, how do they feel, what is going on in the scene you’re drawing? This may require you to think outside of the box in terms of what you consider “anime art.” Of course, you may be so used to seeing pin-ups of popular moe characters that that is all you can visualize in your head, so you may need to take a break from social media and to instead visit your local art museum or an online gallery of art unrelated to anime.

If you still want to look to Japan and anime for visual inspiration without the moe saturation, there are plenty of artists that draw in styles that could be considered anti-moe. Such artists include Taiyō Matsumoto (Tekkonkinkreet, Ping Pong), Inio Asano (Solanin, Goodnight Punpun), Takehiko Inoue (Slam Dunk, Vagabond) and various others. If you’re more interested in animation rather than the comic book form, there’s anime such as Kaiba which has a very surreal art style or Aku no Hana which uses the rotoscope technique to enhance the show’s eerie, dark tone. There are also online communities and contemporary art movements that further push anime to be even less moe or to become something different entirely. This is just one solution I have given, however, the best thing one can do is change how one sees the world – to see it how God sees it, rather than in the way that man does.

Writing for Ascension Press, Fr. Thomas J. Loya, STB writes:

To “see sacramentally” is to see as Adam and Eve first saw before they sinned. It is to see as God saw when he created everything to his image, to reflect his glory […]

In the writings of St. John Paul II, a man of the arts in his own right, he reminds us that the naked human body is not in itself an occasion for lust. Rather, it is how the body is presented and how it is received. Although St. John Paul II cautions that the use of the naked human body in art poses a particular moral challenge of intention and purity, the use of the naked human body in art is not in itself pornographic or an occasion for lust…

This view of seeing the body sacramentally comes from The Theology of the Body, a collection of teachings by St. Pope John Paul II. The teachings go in depth about how the body is viewed and used in Sacred Scripture to reveal God’s plan, as well as how to see our own bodies and the bodies of others in contemporary times as the world has become more secularized. Fr. Loya continues:

Seeing all of life, in particular the human body, “sacramentally” is to see things in an integrated way, in terms of how something points to and participates in God. It is a way of seeing the beauty and the order of things but then keeping our hands off of it.

So why is this the preferred solution I am offering here? Through everything we’ve examined so far - from Honda’s marriage to a fictional character, to the sexualization of Kurapika and various other characters, which then leads to the normalization of unnatural sexual desires, all of this is rooted in objectification of the body. A desire to treat another person not as a soul but as an object to use for pleasure. Pornography is the “lust of the eyes,” so to speak, impacting real people every day.

This is why I discussed the creeping normality of a typical Dragonball Z fan who finds himself suddenly having lolicon or futa on his hard drive. People will argue with this point and become defensive on social media, vehemently shouting: “It’s not real! Why does it matter, it’s just a drawing!” And to that I do agree. It is just a drawing. However, the implication is just the same. Going back to the image of Kurapika, he is not a real male – but an idealized representation of a human male (a teenager at that). How much worse, then – for the person who collects terabytes of representations of sexualized, violated children on his hard drive?

This is why I am an advocate for the theology of the body, a God-centered view that evokes change in how we see ourselves and humanity. The dangers of moe come from straying too far from ourselves and what it means to be human, to recognize each other. The same-faceness and tropes of moe characters and the databases they exist in make it easy to only desire a fantasy instead of reality. “Real women” can be rude, unattractive, unpredictable. Why choose the former when I can have something else that is safe, easy, and comfortable instead?

Pornography and moe, in essence, offer the same thing to their consumer, just on different extremes. With pornography being a replacement for sexual gratification, while moe fills the gap for emotional needs. If this article were to be any longer, this list could go on as to what those emotional needs are and how they are met through moe, such as childhood needs, parental needs, lack of friendship, etc. This then would explain the popularity of the Slice of Life genre especially among working-age, single men.

I want to conclude by saying that I am not anti-anime nor am I anti-moe. I’ve been watching anime for a long time without even realizing it, from the Pokémon and Yu-Gi-Oh! anime when I was a kid to Death Note when I was in middle school. Embarrassing as this is to say, I was part of an anime club in my high school with my friends and did go to anime conventions and cosplay during those years. I don’t hate the fans or fandom in general, but it’s not my identity and I don’t think it ever was the center of my identity. I think it’s important for people to realize that they can detach or rise above materialism and capitalism (a system that wishes to have them in shackles for profit).

So what will I do? If I believe that there is such a strong correlation between sexuality and moe – a problem that doesn’t seem to be going away any time soon, should I just not be involved in anime fandom? The answer is yes and no. Yes, in that there will always be anime I will enjoy and come back to as “comfort television” or “comfort manga.” Engaging stories and artwork come from all around the world, so I see no reason to have a bias against Japan because of some bad fruit. But at the same time, I can’t become attached in the ways that a weeaboo or an otaku become attached. I love Azumanga Daioh, but I don’t see myself starting a podcast or starting a blog endlessly talking about how much I enjoy it.

That’s how I think most fans should treat this hobby. It should be a mild interest. We don’t need large communities, we don’t need endless fights about “gatekeeping” or what is or what isn’t tolerable in the “fandom.” It’s all needless. An individual should be able to just enjoy a simple book or show and be entertained or learn something. But with all that said, my primary goal with this article was to get you to think about the realm of acceptability. How far are you willing to tolerate the foreign, the uncomfortable, so long as you can stay within the comfort of the fandom? Is the fandom itself or “community” that you belong to a source of discomfort, and how long have you allowed yourself to accept that type of behavior?

This is why – although I enjoy HunterXHunter – I refuse to call myself a HunterXHunter fan. I see no reward or benefit from being in communion with people who sexualize characters I’ve come to care about. I enjoy the story and the world in my own way, on my own terms without the need to belong to a “community.” After realizing that my favorite series had seemingly been invaded by fujoshis (the female otaku equivalent) I voluntarily left the HunterXHunter community. I started to look further, examining the behaviors of the fandom and the art that was being made. That was when I came to realize that there were major problems inherent to anime and manga that made the situation I was previously in possible.

Anime fandom cannot change unless there is a massive cultural shift – but you can change how you see things, how you see people, and how you see the world. At the very beginning of this article, I posted a clip of Chiyo singing Tsukurimashou (Let’s Make Something!). The reason is because I just find it cute and I think it best represents what moe should be. It’s something sweet and endearing that you can show your daughter or niece and they might enjoy it, too. This explains the near-global recognition of Studio Ghibli; a studio that embraces the wholesome side of moe while giving just enough of a push or an edge to their storytelling so as to keep it engaging and entertaining for all audiences (not just children).

One thing I am certain of is that most otaku or weeaboos would rather have something else in their life; be it a real woman, an enjoyable hobby or skill, maybe just to be accepted. There’s a massive hole in their heart that moe has filled – but it can only be filled for so long before it becomes empty again. I’ve brought some solutions to the table for this person to consider, such as a change in their relationship with anime or to have a relationship with God in a spiritual sense. Ultimately, what needs to happen for change is for the otaku to have a new identity that isn’t tied to their sexuality (or lack thereof). The otaku will eventually come to understand that fiction is just fiction; a realm separate from reality. Once they have made the proper changes needed in their life and in their perception (i.e. realizing the errors of objectification, how damaging pornography is to the interior of their person and to others), then they can come back to their favorite anime with the knowledge that it’s just another form of entertainment.

This post is just raising awareness to a much larger issue I’ve seen happening in the online space. A lot of this post wouldn’t have been made without the translation work and research from Patrick W. Galbraith. If you want to learn more about the Theology of the Body I will include more information down below. All links and resources used will be listed down below.

- - Midwest

Sources:

Moe Manifesto: An Insider’s Look at the Worlds of Manga, Anime, and Gaming (Galbrath, 2014)

http://www.japanesestudies.org.uk/articles/2009/Galbraith.html

https://medium.com/read-event-horizon/explainer-2-hiroki-azuma-and-the-database-animal-2716b8e6ecd5

https://www.davidbrin.com/nonfiction/neoteny1.html

https://artsammich.blogspot.com/2015/03/baby-face-bias.html

http://www.cjas.org/~leng/hikiko.htm

https://www.cjas.org/~leng/otaku-origin.htm

https://jobsinjapan.com/living-in-japan-guide/the-world-of-anime-enthusiasts-how-otaku-went-from-stereotypes-to-mainstream/

https://allthatsinteresting.com/tsutomu-miyazaki

https://dic.pixiv.net/en/

https://www.japanesewithanime.com/2020/01/tareme.html

https://tvtropes.org/pmwiki/pmwiki.php/Main/OnlySixFaces

https://gamezone.com/originals/gta-5-releases-a-wild-jack-thompson-appears-gamers-addiction-has-made-them-retarded/

https://media.ascensionpress.com/2019/06/18/an-artist-turned-priest-proposes-an-ethos-of-seeing/

Theology of the Body Resources:

https://tobinstitute.org/

https://theologyofthebody.net/